Probability Review

Lecture 02

January 23, 2026

Review

Last Class

- Class Motivation

- Policies (see syllabus if class missed)

Probability “Review”

What is Uncertainty?

…A departure from the (unachievable) ideal of complete determinism…

— Walker et al. (2003)

Types of Uncertainty

| Uncertainty Type | Source | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Aleatory uncertainty | Randomness | Dice rolls, Instrument imprecision |

| Epistemic uncertainty | Lack of knowledge | Climate sensitivity, Premier League champion |

Sources of Uncertainty

- Model structures

- Parameters

- Data collection (measurement/observation errors)

Probability

Probability is a language for expressing uncertainty.

The axioms of probability are straightforward:

- \(\mathcal{P}(E) \geq 0\);

- \(\mathcal{P}(\Omega) = 1\);

- \(\mathcal{P}(\cup_{i=1}^\infty E_i) = \sum_{i=1}^\infty \mathcal{P}(E_i)\) for disjoint \(E_i\).

Probability Distributions

Distributions are mathematical representations of probabilities over a range of possible outcomes.

\[x \to \mathbb{P}_{\color{green}\mathcal{D}}[x] = p_{\color{green}\mathcal{D}}\left(x | {\color{purple}\theta}\right)\]

- \({\color{green}\mathcal{D}}\): probability distribution (often implicit);

- \({\color{purple}\theta}\): distribution parameters

Sampling Notation

To write \(x\) is sampled from \(\mathcal{D}(\theta)\): \[x \sim \mathcal{D}(\theta)\]

For example, for a normal distribution: \[x \overset{\text{i.i.d.}}{\sim} \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma)\]

Probability Density Function

A continuous distribution \(\mathcal{D}\) has a probability density function (PDF) \(f_\mathcal{D}(x) = p(x | \theta)\).

The probability of \(x\) occurring in an interval \((a, b)\) is \[\mathbb{P}[a \leq x \leq b] = \int_a^b f_\mathcal{D}(x)dx.\]

Important: \(\mathbb{P}(x = x^*)\) is zero!

Probability Mass Functions

Discrete distributions have probability mass functions (PMFs) which are defined at point values, e.g. \(p(x = x^*) \neq 0\).

Cumulative Density Functions

If \(\mathcal{D}\) is a distribution with PDF \(f_\mathcal{D}(x)\), the cumulative density function (CDF) of \(\mathcal{D}\) is \(F_\mathcal{D}(x)\):

\[F_\mathcal{D}(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_\mathcal{D}(u)du.\]

Relationship Between PDFs and CDFs

Since \[F_\mathcal{D}(x) = \int_{-\infty}^x f_\mathcal{D}(u)du,\]

if \(f_\mathcal{D}\) is continuous at \(x\), the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus gives: \[f_\mathcal{D}(x) = \frac{d}{dx}F_\mathcal{D}(x).\]

Quantiles

The quantile function is the inverse of the CDF:

\[q(\alpha) = F^{-1}_\mathcal{D}(\alpha)\]

So \[x_0 = q(\alpha) \iff \mathbb{P}_\mathcal{D}(X < x_0) = \alpha.\]

Measures of Central Tendency

Common measures of “typical” values of a function \(f\) of a random variable \(Y \sim p_{\mathcal{D}}(y)\):

- Mean (or expected value): \[\mathbb{E}[f(Y)] = \int_Y f(y) p(y) dy\]

- Median: \(q(0.50)\)

- Mode: \(\max_{Y} p(f(Y))\)

More On Distributions

Distributions Are Assumptions

Specifying a distribution is making an assumption about observations and any applicable constraints.

Examples: If your observations are, then the most common choices are:

- Continuous and fat-tailed? Cauchy distribution

- Continuous and bounded? Beta distribution

- Sums of positive random variables? Gamma or Normal distribution.

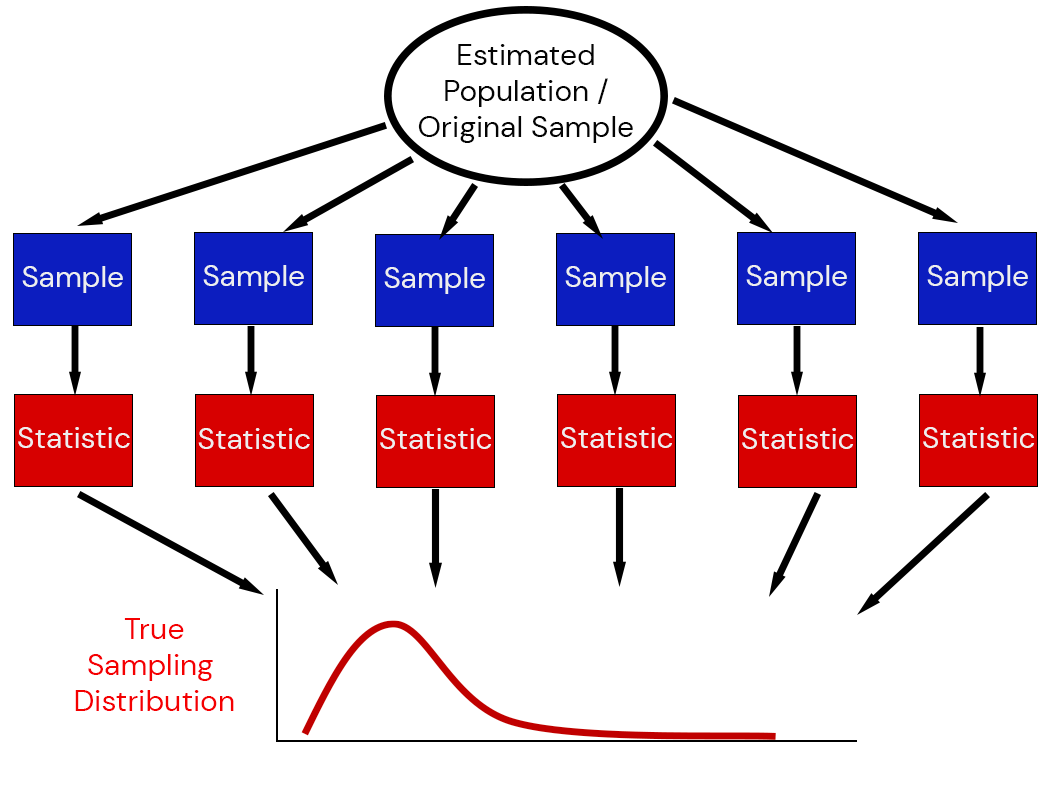

Statistics of Random Variables are Random Variables

The sum or mean of a random sample is itself a random variable:

\[\bar{X}_n = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n X_i \sim \mathcal{D}_n\]

\(\mathcal{D}_n\): The sampling distribution of the mean (or sum, or other estimate of interest).

Sampling Distributions

Illustration of the Sampling Distribution

Likelihood

Likelihood

How do we “fit” distributions to a dataset?

Likelihood of data to have come from distribution \(\mathcal{D}\) with pdf \(f(\mathbf{x} | \theta)\):

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{x}) = \underbrace{f(\mathbf{x} | \theta)}_{\text{PDF}}\]

In other words: likelihood evaluates parameters conditional on data, PDF evaluates data conditional on parameters.

Normal Distribution PDF

\[f_\mathcal{D}(x) = p(x | \mu, \sigma) = \frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{x - \mu}{\sigma}^2\right)\right)\]

Likelihood of Multiple Samples

For multiple (independent) samples \(\mathbf{x} = \{x_1, \ldots, x_n\}\):

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta | \mathbf{x}) = \prod_{i=1}^n \mathcal{L}(\theta | x_i).\]

Likelihood Example

| Distribution | Likelihood |

|---|---|

| \(N(0, 1)\) | 3.7e-11 |

Likelihood Example

| Distribution | Likelihood |

|---|---|

| \(N(0, 1)\) | 3.7e-11 |

| \(N(-1, 2)\) | 5.9e-10 |

Likelihood Example

| Distribution | Likelihood |

|---|---|

| \(N(0, 1)\) | 3.7e-11 |

| \(N(-1, 2)\) | 5.9e-10 |

| \(N(-1, 1)\) | 1.2e-13 |

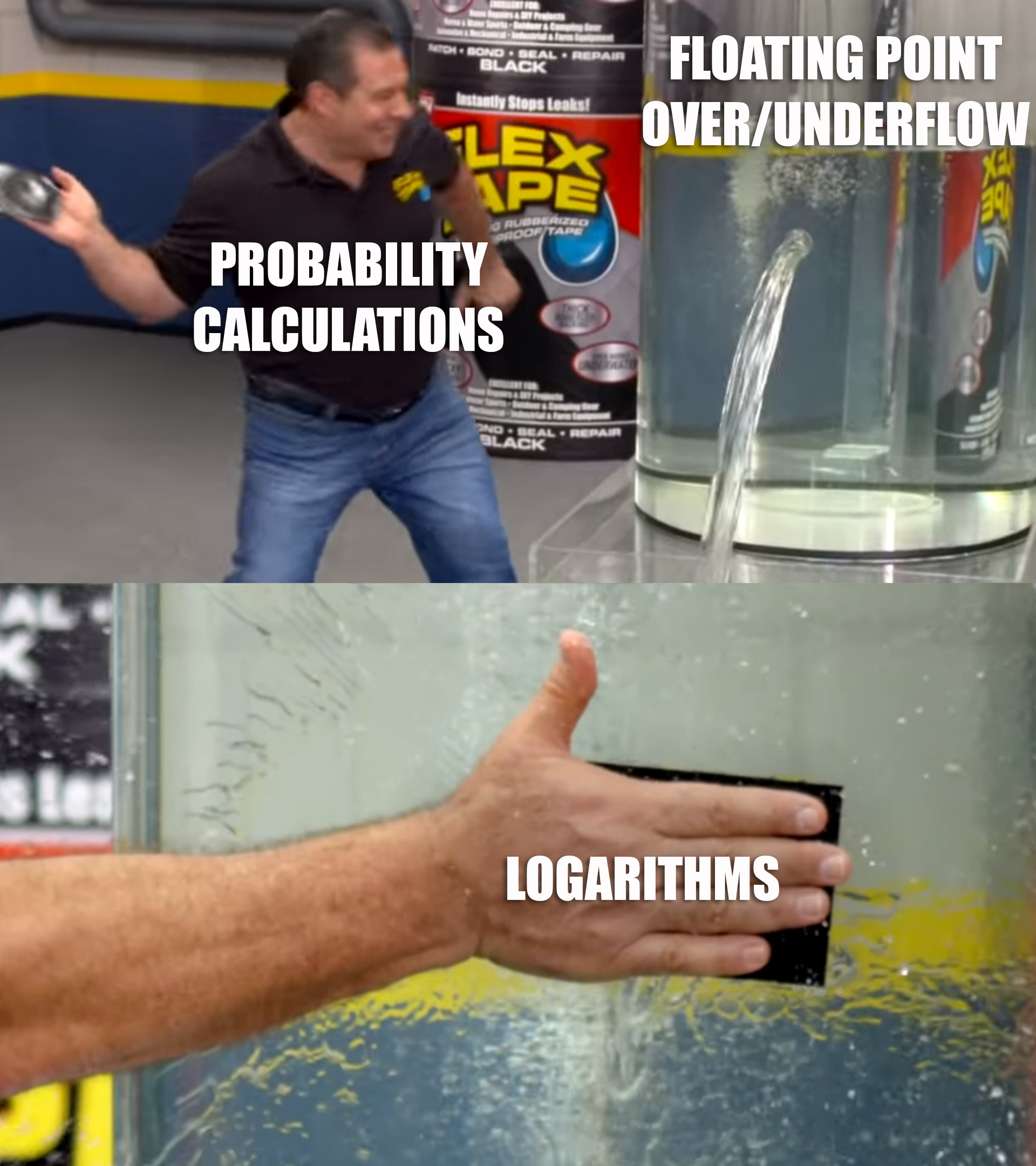

Log-Likelihood

Likelihoods get very small very fast due to multiplying small numbers.

This is a computational problem due to underflow.

We use logarithms to avoid these issues: compute \(\log \mathcal{L}(\theta | x)\).

Upcoming Schedule

Next Classes

Next Week: Exploratory Data Analysis

Assessments

Homework 1 due next Friday (2/6).

Reading: