GLM (Poisson Regression) Example

Lecture 10

February 13, 2026

Review

GLMs

- Use linear model to specify (usually transformed) parameters of a non-Gaussian distribution.

- Can be more challenging to specify, interpret, and check.

- Examples: Poisson, Binomial regression, but almost unlimited combinations of distribution + link possible.

Poisson Regression Example

- The data is overdispersed relative to a Poisson distribution.

- But a Poisson GLM may produce overdispersed data, since every observation has a different \(\lambda_i\) (hence mean and variance.)

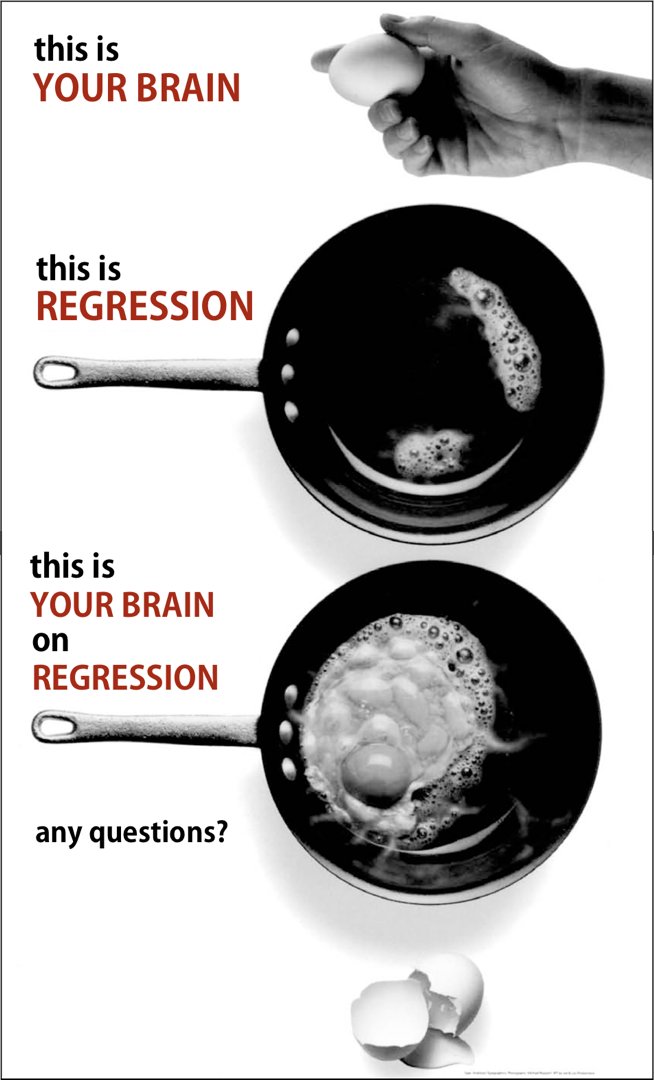

Be Cautious…

- Over-relying on plots like histograms can lead to mis-specifying GLM dynamics.

- Think of linear regression: the question is not if the data are Gaussian but the residuals.

Source: Richard McElreath

Model Specification

We might hypothesize that the number of fish caught is influenced by the number of children (noisy, distracting, impatient) and whether the party brought a camper.

\[\begin{align*} y_i &\sim \text{Poisson}(\lambda_i) \\ f(\lambda_i) &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 \text{child}_i + \beta_2 \text{camper}_i \end{align*} \]

\(\lambda_i\): positive “rate”

\(f(\cdot)\): maps positive reals (rate scale) to all reals (linear model scale)

Fitting the Model

function fish_model(params, child, camper, fish_caught)

β₀, β₁, β₂ = params

λ = exp.(β₀ .+ β₁ * child + β₂ * camper)

loglik = sum(logpdf.(Poisson.(λ), fish_caught))

end

lb = [-100.0, -100.0, -100.0]

ub = [100.0, 100.0, 100.0]

init = [0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

optim_out = optimize(θ -> -fish_model(θ, fish.child, fish.camper, fish.fish_caught), lb, ub, init)

θ_mle = optim_out.minimizer

@show round.(θ_mle; digits=2);

@show round.(exp.(θ_mle); digits=2);round.(θ_mle; digits = 2) = [0.91, -1.23, 1.05]

round.(exp.(θ_mle); digits = 2) = [2.48, 0.29, 2.87]Interpretation of Coefficients

Since \(\log(\lambda_i) = \sum_j \beta_j x^i_j\):

\(\exp(\beta_j)\) says how much a unit increase in \(x_j\) multiplies the rate (hence expected value).

So \(\beta_1 =\) -1.2 says that each extra child reduces the expected number of fish caught by a factor of 0.3.

Predictive Checks To Evaluate Model

- Linear regression: model checking was straightforward: residuals should have been Gaussian distributed.

- GLMs: Less clear how to check distributional assumptions.

Strategy: check predictive distribution of relevant summary statistic(s) by simulation; do you capture the empirical statistic?

Predictive Checks

In other words, for some statistic \(T\):

- Estimate \(\hat{T}\) from the data.

- Simulate synthetic datasets using your model and calculate \(\tilde{T}_n\) for each one;

- Examine the distribution of \((\tilde{T})\) to see where \(\hat{T}\) falls.

Teaser: This is closely related to the idea of a \(p\)-value…

Checking Proportion of Zero Fish

Code

# simulate samples for each P

λ = exp.(θ_mle[1] .+ θ_mle[2] * fish.child .+ θ_mle[3] * fish.camper)

# draw 10,000 samples for each

fish_sim = zeros(10_000, nrow(fish)) # initialize matrix to store simulations

for i = 1:nrow(fish)

fish_sim[:, i] = rand(Poisson(λ[i]), 10_000)

end

# calculate frequency of zeros

fish_zeros = mapslices(row -> sum(row .== 0) / length(row), fish_sim; dims=1)

histogram(fish_zeros', xlabel="Proportion of Zeros", ylabel="Count", label=false)

vline!([sum(fish.fish_caught .== 0) / nrow(fish)], color=:red, linewidth=3, label="Empirical Statistic")Figure 2: Predictive distribution for fitted fish model.

What Was The Problem?

- The model produces far fewer zero-fish counts than the data.

- This is typical of a lot of environmental count data; often have far more zeros than would be expected from a Poisson regression.

- Alternative: Use a zero-inflated model.

Zero-Inflated Models

Mixture Models

When we have two different data-generating processes which produce the same observable outcome, may need to use a mixture of two distributions to capture outcome.

Distribution 1: \(\mathcal{D}_1\) with likelihood \(L_1(\theta_1 | y)\).

Distribution 2: \(\mathcal{D}_2\) with likelihood \(L_1(\theta_2 | y)\).

Mixture Model Likelihood

Then if \(y_i \sim \mathcal{D}_1\) with probability \(p_i\), \(y_i \sim \mathcal{D}_2\) with probability \(p_{i-1}\).

\[L(p_i, \theta_1, \theta_2) = \prod_{i=1}^n \left(p_1 L_1(\theta_1 | y_i) + p_2 L_2(\theta_2 | y_i)\right)\]

Fitting Mixture Models

This can get complicted (and require more complicated algorithms) when with many or similar mixture components. But our case is easier!

Example: Mixture Rationale

- Some groups don’t fish, which guarantees no fish.

- Probability of fishing is influenced by size of group.

- If a group fishes, then there’s a Poisson process for the number of fish they catch.

- Expected fishing influenced by children and campers.

Zero-Inflated Poisson

This is a mixture between a Poisson and point-distribution (Dirac distribution) at zero.

\[\begin{aligned} y_i &\sim p_i \text{Dirac}(0) + (1 - p_i) \text{Poisson}(\lambda_i) \\ \text{logit}(p_i) &= \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 \text{persons}_i\\ \log(\lambda_i) &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 \text{child}_i + \beta_2 \text{camper}_i \end{aligned}\]

ZIP Likelihood

If \(y = 0\):

\[\mathcal{L}(p_i, \lambda_i | y_i = 0) = p_i + (1 - p_i) \overbrace{e^{-\lambda_i}}^{\text{Poisson zero likelihood}}\]

If \(y > 0\):

\[\mathcal{L}(p_i, \lambda_i | y_i > 0) = (1 - p_i) \underbrace{\frac{\lambda_i^{y_i}e^{-\lambda_i}}{y_i!}}_{\text{Poisson likelihood}}\]

Fitting ZIP

invlogit(x) = exp(x) / (1 + exp(x))

ZeroInflated(p, λ) = MixtureModel([Dirac(0), Poisson(λ)], [p, 1 - p])

function fish_model_zip(params, persons, child, camper, fish_caught)

α₀, α₁, β₀, β₁, β₂ = params

p = invlogit.(α₀ .+ α₁ * persons)

λ = exp.(β₀ .+ β₁ * child .+ β₂ * camper)

ll = sum(logpdf.(ZeroInflated.(p, λ), fish_caught))

return ll

end

lb = [-100.0, -100.0, -100.0, -100.0, -100.0]

ub = [100.0, 0.0, 100.0, 100.0, 100.0]

init = [5.0, -2.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

optim_out = optimize(θ -> -fish_model_zip(θ, fish.persons, fish.child, fish.camper, fish.fish_caught), lb, ub, init)

θ_mle = optim_out.minimizer

@show round.(θ_mle; digits=2);

@show round.(exp.(θ_mle); digits=2);round.(θ_mle; digits = 2) = [1.3, -0.56, 1.6, -1.04, 0.83]

round.(exp.(θ_mle); digits = 2) = [3.66, 0.57, 4.94, 0.35, 2.3]Evaluating Model Fit

Code

# simulate samples for each P

p = invlogit.(θ_mle[1] .+ θ_mle[2] * fish.persons)

λ = exp.(θ_mle[3] .+ θ_mle[4] * fish.child .+ θ_mle[5] * fish.camper)

# draw 10,000 samples for each

fish_sim = zeros(10_000, nrow(fish)) # initialize matrix to store simulations

for i = 1:nrow(fish)

u = rand(Uniform(0, 1), 10_000)

for j = 1:10_000

if u[j] < p[i]

fish_sim[j, i] = 0.0

else

fish_sim[j, i] = rand(Poisson(λ[i]))

end

end

end

# calculate frequency of zeros

fish_zeros = mapslices(row -> sum(row .== 0) / length(row), fish_sim; dims=1)

histogram(fish_zeros', xlabel="Proportion of Zeros", ylabel="Count", label=false)

vline!([sum(fish.fish_caught .== 0) / nrow(fish)], color=:red, linewidth=3, label="Empirical Statistic")Interpretation of Check

- This is much better, but is only one test.

- A model has more evidence for it if it passes multiple checks.

- But none of this can “prove” a model is right: need to rely on hypotheses and EDA to propose a sensible model.

Key Points and Upcoming Schedule

Key Points

- Zero-inflation can address problems where data have more zeros than GLM distribution would suggest.

- Simple version of a mixture model.

Upcoming Schedule

Monday: No class, enjoy break.

Next Two Weeks: Extreme Values

HW2: Due 2/20

Project Proposal: Due 2/27